Meet The Woman Who Asked All The Wrong Questions At The Right Time

Ethel Payne set the bar for journalism, as she broke boundaries for Black women in the news world.

From a young age, Payne challenged herself in school. She wanted to learn new material, despite the limiting economic circumstances she faced. Her family could not afford to put all their children in college, so she faced the conditions head-on and worked around them. She attended the Gloria Biblical Institute where she took rigorous classes that sparked her desire to help others.

There wasn’t one place that Payne could be tied down to as her affinity to learn was unstoppable. She wanted to explore the different career paths that would allow her to help others. She worked as a matron in the State Training School for Girls, moved on to being a nursery school teacher in public schools, and then became a junior librarian once she completed a library training program.

With all this experience, Payne’s role in the civil rights movement didn’t form until she met A. Philip Randolph in 1941. Randolph was an active member of the civil rights and labor movement. Both worked together on the March On Washington which intended to end discrimination in the war and military industries. Working with Randolph proved to be transformative as it was the platform Payne launched from as she became increasingly involved in advocating the end of segregation.

Payne continued to dabble in different industries, eventually having her work picked up by The Chicago Defender. While in Tokyo, she wrote journals documenting the American clubs and living conditions of Black soldiers. Reporters from The Chicago Defender published her findings, which brought over great controversy of the segregated conditions because President Truman already ruled against it. Her coverage marked the beginning of the many rules she would break as she rose to the forefront of journalism. Shortly after her observations were published, she was offered a position at The Chicago Defender in 1951.

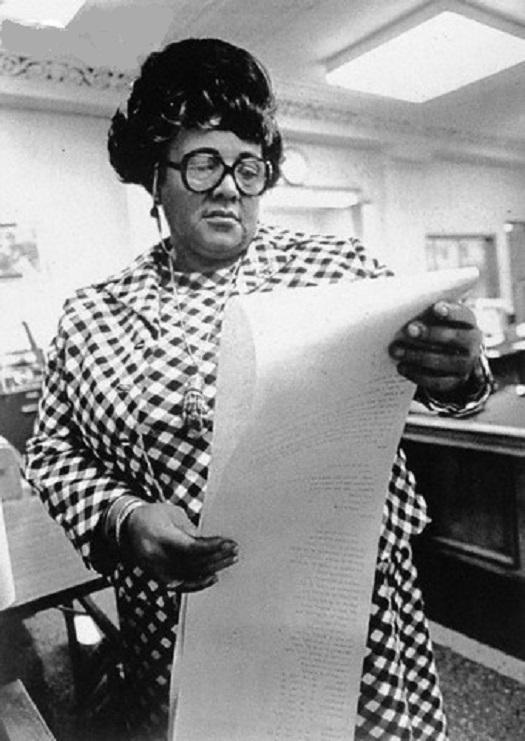

Payne soon moved up in the world of journalism. She was assigned features, but soon grew restless. In 1953, she went to Washington DC to cover politics. She was one of the three African-American correspondents to cover White House politics. Once she got there, she did not remain in the background as she asked the questions no one wanted to ask. She soon became known as the correspondent who constantly asked President Eisenhower questions about the visible segregation in the country and what the government was going to do.

She developed a reputation as being a fearless questioner, and eventually struck a nerve with the White House. Payne asked why the government wasn’t supporting a ban on segregation of interstate travel, to which President Eisenhower responded that civil rights matters were of special interests. The remarks hit the papers, which angered the White House. They tried to discredit her work, but she could not be brought down. Her tenacity made her a fierce journalist, one who was known for asking “wrong” questions at the right time to spur change. She laid off the White House, and moved on to reporting on civil rights issues in the South and news overseas.

In 1955, she was sent to Indonesia to cover the Bandung Conference; she was the first Black correspondent to cover such an event and the first Black woman to cover the Vietnam War.

When she returned from her travels overseas, she homed in on the Civil Rights Movement. “The South At The Crossroads” chronicled the segregation in the South, ranging from the Montgomery bus boycott to the Little Rock crisis. Her constant coverage propelled her past her white colleagues in the realm of “seg beat”, or the part of news that documented segregation. Her stories quickly gave her the title of “The First Lady of Black Press.”

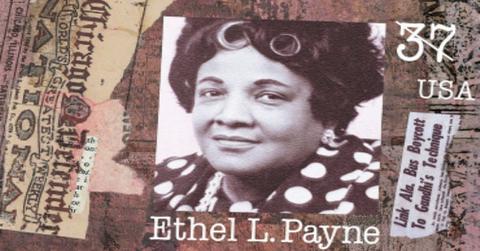

Her list of firsts continued as she became the first African-American female radio and television commentator at CBS in 1972. She worked on the network until 1978, when she left to work on her own self-syndicated column. In 1988, she was inducted in the District of Columbia’s Hall of Fame. She also won a range of awards from the Chicago Council on Foreign Affairs and the National Association of Black Journalists. To emphasize the importance of Payne’s work, the Postal Service chose her as one of the four journalists to be featured on stamps.

Even after her death, Payne will continue to be remembered as an instrumental force in creating paths for black women in the media industry. Her relentless questioning and drive to be at the front of reporting paved the way for future women.