How ACEs Impact Your Health Over Time, And Why A Strong Support System Is Important For Prevention

We’re in a time of great reckoning. As the country comes face to face with it’s past, and the spirit of unearthing that which has laid dormant, it may be a great time of personal reflection for us all.

Recently, I learned about something known as Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs. ACEs are traumatic events in a child’s life, including child abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), child neglect, parent or household mental illness, witnessing domestic violence, having a parent or family member in jail, parent separation or divorce, and death of a parent or sibling.

Exposure to early adversity affects the body and brains of children. The impact can linger into adulthood. Experiencing ACEs has been found to increase the risk of:

- Teen pregnancy

- Alcoholism

- Smoking

- Misuse of prescription drugs

- Illicit drug use

- Depression

- Heart disease

- Liver disease

- Intimate partner violence

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Suicide attempts/death by suicide

Some of those issues are among the leading causes of death in the United States and the trigger—ACEs—is preventable and treatable.

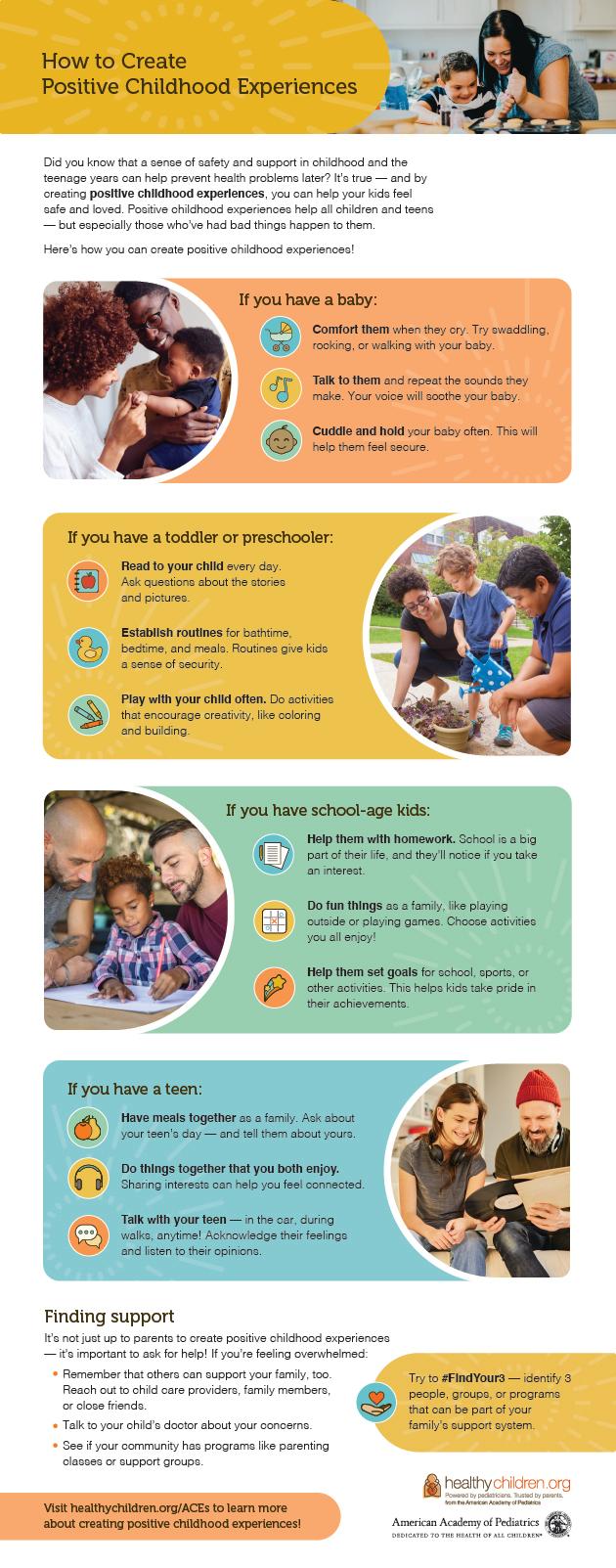

It’s more common than you think. A study of 144K adults released by the CDC found 61% reported at least one ACE, and 16% had four or more ACEs. Although it can be unavoidable to eliminate experiences such as death within a child’s life, it is possible to mitigate an ACE’s effect. It comes down to providing children with strong support systems through organizations and individuals who can provide positive childhood experiences. Support networks are important.

“In the words of Dr. Robert Block, the former president of the Academy of Pediatrics, Adverse Childhood Experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today, and for a lot of people, that’s a terrifying prospect,” explains pediatrician Nadine Burke Harris in a recent TED Talk focused on ACEs.

In learning about ACEs, I turned the lens inward on my own childhood experiences and what support networks helped me over the years. As a child of a single mother, I am more than grateful for the positive experiences I had growing up in New York City. This doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s truly dependent on raising a child within a supportive community.

Thanking My Three

I was around three years old when my parents divorced. I was a resilient child who turned my circumstances into fuel to succeed. I was four years old when I taught myself how to read before attending school. I taught myself with a program called Hooked On Phonics after seeing the commercial on television. Living in New York City, there are words everywhere due to the billboards all over the city, and I wanted to begin to understand what the world around me was saying.

From that point on, I read anything I could get my hands on. I’d carry a book with me everywhere. It was incredible to get soaked up into another world. By the time I was in first grade, I was reading chapter books. The adults in my life praised me for this trait, but I distinctly remember one in particular, my aunt, who dived into the subject with me.

I thank my aunt, Angela Roberson, for always showing an interest in my reading and comprehension development. She was an English teacher, so it was refreshing to speak with her in-depth about symbolism, story structure, and plot development. During the summers, she assigned my cousins and me books to read. To top it off, we were required to complete book reports! For me, this was a welcome experience. Unfortunately, my cousins didn’t feel as enthusiastic (LOL).

Speaking of summers, I had magical summers. My mother made sure of it. From the age of 6 until I was 12 years old, I spent my summers in Chesterfield, Virginia at my grandparents’ home. I was joined by my little brother and two cousins. Those summers were filled with bike rides, almost daily visits to the pool, and complete with a season pass to the local amusement park, Kings Dominion. My grandmother made sure we had a balance of fun and enriching activities all summer. We often visited local museums and parks. We went to the movies. The days were long and always filled with something that filled us as children.

I am grateful for that experience, especially reflecting as an adult. It gave me a chance to truly be a carefree kid and get outside. There were no worries about busy streets or any of the issues that come with being a city kid. I thank my grandmother, Elizabeth Pugh, for providing those experiences.

I never wanted those summers to end because it meant school was starting again. While I did well in school, I never actually liked it. I didn’t like anything I “had” to do. However, teachers played a major role in providing positive experiences. As a student of New York City public schools, I was lucky that my schools were institutions with quality education. Even so, there was one teacher in particular who spoke with my mom about putting me in a different type of environment for gifted children.

My mom often jokingly tells the story of my time in Kindergarten. On the first day, as other children were crying, I was anxious to get started, simply turning around to her and saying “bye” as I walked boldly into the classroom. After that year, I transferred to a private school, but not before the school practically begged my mom to keep me there. Then, my family moved to a Queens suburb, and I was enrolled in the local public school for 2nd grade. It was my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Espinet, who took my mother aside and told her, “She doesn’t belong here.”

I remember Mrs. Espinet as tough. She had high expectations and higher standards. I wasn’t particularly great at math, and I remember how hard I studied for her pop up multiplication quizzes. If she called on us, we had to pop up and recite aloud any times table she requested. But I was better for it. And Mrs. Espinet saw something in me and didn’t let it simply pass. She explained to my mother that I was too advanced for the level of work, and if I didn’t get placed in a school that would challenge me academically, I would become bored and likely lose interest in education altogether.

With that prompting, my mother immediately signed me up for a gifted school, which put me ahead academically and created the foundation for the discipline and appreciation for hard work that I still have today. I thank my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Espinet, for pushing my mother to put me in a challenging environment that groomed me for excellence.

Prevention And Treatment – What You Can Do

Awareness of ACEs and the ways to prevent and mitigate the negative effects can have a major impact on the health of children as they grow into adults. It’s nothing to be ashamed of if you or someone you love has dealt with ACEs.

“The scope and scale of the problem seems so large that it feels overwhelming to think about how we might approach it, but for me, that’s actually where the hope lies because when we have the right framework when we recognize this to be a public health crisis then we can us the right toolkit to come up with solutions,” shared Dr. Harris.

The solution is as simple as having reliable supportive adults creating positive environments for growth. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), recommends aiming for three, but any number is a step in the right direction. I reflected here on my development and used my story as a way to thank my three.

How will you #thankyour3? One way is to simply pay it forward. As an adult, you can be one of a child’s three. Serving as a mentor or spending some regularly scheduled time with a young niece or cousin can make a huge difference.

“This is treatable, this is beatable,” Dr. Harris further shares in her talk. “The single most important thing we need today is the courage to look this problem in the face to say this is real and this is all of us.”

[Editor’s note: This article is made possible with support from the American Academy of Pediatrics through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All opinions are the writer’s own.]