Iconic Rosie The Riveter Gets An Important Update

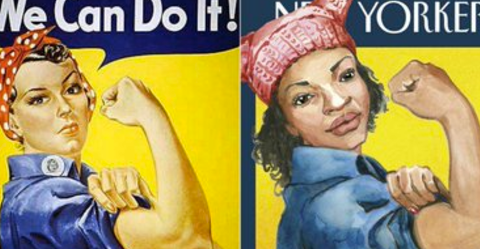

After 75 years, feminist symbol Rosie the Riveter got an update. And it is pretty darn intersectional.

This week’s cover of The New Yorker will feature a much more modern version of Rosie the Riveter – a woman of color in the infamous Rosie blue jumpsuit – arm flexed with fierce feminine power -and the iconic pink knitted pussy hat so synonymous with the women’s march clad atop her curly hair.

Although The New Yorker received many images of Rosies after the Women’s March (the headlining story for which this week’s issue will cover), Maine-based artist Abigail Gray Swartz’s depiction was the only one that featured a woman of color.

“It was just a no brainer,” Swartz says of her reasoning to change Rosie from a white woman to an African American woman in an interview with HuffPo, “I want to paint Rosie as a symbol of the Women’s March and she should look like this.”

The New Yorker editor Francoise Mouley explained that it was because Swartz’s art took an intersectional approach that it stood out amongst the many Rosie contributions the New Yorker received: “She shaped it in a way that took it one step further than the others,” Mouley explained in an interview with The Portland Press.

The intersectionality of this Rosie holds especially important significance during a time when feminism – a movement traditionally symbolized in pop culture through white women’s voices – is surging into the frontlines of popular political debate.

Though it is incredible that women are leading many of the political and cultural battles in our nation, (and that our culture is celebrating their achievements), it is also important for people to understand that the idea of gender equality reaches much further than the term ‘gender.’ The core of intersectional feminism seeks to empower all kinds of women from diverse backgrounds with diverse needs – not just one particular race, culture, or idea of womanhood that happens to represent the majority.

As The Grio notes, “the image is not only significant because of its feminist message but because of the message of intersectionality at a time when feminism is coming up against the problem of how to address the fact that women of color have historically been left out of the movement and even actively pushed out of it.”

This image puts an intersectional Rosie smack dab in the center of it all.

Yet for all it’s cultural significance in this very important and inspiring time for feminism, this updated image of Rosie almost didn’t happen. Although Swartz describes being featured in The New Yorker as a longtime dream, she didn’t anticipate it happening and sent her painting into the publication on a whim.

According to The Portland Press, Swartz first came into contact with The New Yorker staff at a workshop at the Maine College of Art last summer, which eventually led her to arts editor Francoise Mouley. Mouley is also the arts editor of a comic and graphics publication Resist!, which features political commentary from female artists. After attending a sister march in Maine, Swartz felt invigorated to produce more artwork, and sent it off to Mouley with little inclination she would hear back from her. 72 hours and a few revisions later, Swartz was given notice her work would be published in The New Yorker.

The original Rosie the Riveter poster took years to gain symbolic fame, and much of it’s feminist aura is embedded in myth. Originally a war-time poster commissioned by the Westinghouse Company’s War Production Coordinating Committee in 1942, it stood as part of a series of motivational propaganda. The poster hung in the Westinghouse headquarters as motivation for male and female employees for no more than two weeks, when it was taken down and stored in a closet until it was rediscovered in the 80s. The Rosie Poster – originally believed to be called “We Can Do It”, subsequently promptly rose to fame and became a symbolism for feminism.

The latest issue of The New Yorker magazine can be found here.