Op-Ed: Marching For The Black Women And Girls In The Margins

In 2016, I was invited to speak at Planned Parenthood’s centennial conference on the topic of immigrant women and health care.

In a three minute speech, I shared my anxieties of being deported, including overhearing someone ask, “Can you get me ice?” and thinking ICE — Immigration Customs Enforcement. For so long, I did not form friendships because when you get close to people, you tend to want to share your secrets. When you share a secret like being undocumented with someone, you have to be careful to never upset that person, because if you do, they could call ICE and get you deported. I didn’t have the privilege of being upset with a friend or breaking up with a boyfriend because it could force me and my family to be deported. I lived in a constant state of fear and anxiety. I talked about how it impacted my mental health and how being undocumented meant I wasn’t able to seek mental health care.

I grew up in Miami, FL, one of the top 10 undocumented cities in the U.S. A vast majority of the 3.8 million immigrants living in Florida are Latin. Prior to advocating for immigration reformation, I had no idea there were Black immigrant populations – families like mine who had never seen a doctor because we didn’t have health insurance. Families who also had several alias names. Families with members who never learned how to drive or drove with the risk of detainment, imprisonment, deportation, or unpaid labor. Families with people who never owned an identification card, or obtained a college degree at a school that does not have an open door policy.

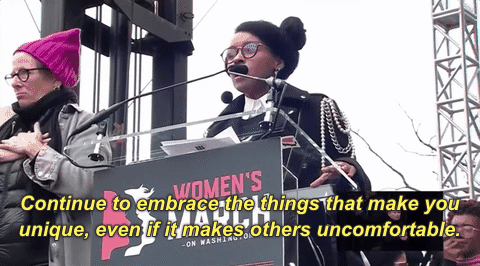

Had it not been for Miami Dade College’s open door policy, I never would have been able to achieve the things that I did, including serving as a U.S. House of Representative Press Assistant and provide legislative support on women and girls issues. During that time, I decided to participate in the Women’s March. I volunteered with the global communications team ensuring we were encouraging women in other countries to hold marches and asking the press to cover the marches at a broad scale. The day before the march, I asked my then boss, Congresswoman Yvette D. Clarke if I could make an obnoxiously large banner with the words Black Women of Congress, and all of the Black Congresswomen could hold it up as they marched. It worked.

The March is largely organized by women of color, the national team including two African-American women, a Palestinian-American-Muslim woman, and an Indian woman. I was excited to be part of such a large movement that included the voices of women like me. It felt empowering and I was emboldended by the sentiment that now, finally, I had found a space where my Brown body would be accepted, protected, and celebrated as part of the larger, diverse framework of American feminism.

Yet there was a striking lack of representation of women from diverse backgrounds in attendance at the Women’s March. Most of the march was in fact, attended by predominantly white women. Yes, there were many Black women there, but certainly not in comparison to white women. Consequentially, one of the biggest critiques of the women’s march made in editorials and movements afterward, was that it felt exclusionary to women of color.

Perhaps one of the more popular critiques came out of the pussyhat movement, a grassroots movement that inspired the “sea of pink” hats came from a lot of white women who had knitted or brought and handed out pussyhats toppled over the Women’s march and people -and the press- ended up focusing on the hats. I was not wearing pink, but I was given a pink pussyhat. I did not wear it simply because it didn’t fit my hair. I can imagine other women of color with large, natural hair not wearing it for the same reason. It was a small nuisance, but a subtle reminder that womanhood is still yet to be defined or understood in a way that promotes all forms of womanhood, and that in some sense, this wasn’t a march that empowered all women, or us as Black women.

Yet the history of women’s marches in America is thwarted with this crushing truth. If you look at photos from the first suffrage parade, you won’t find Black women in any of the photos. You will find white women in beautiful dresses with elongated banners asking for the right to vote. I have searched for photos of Black women in this march and marches in the 20th century but failed to discover any photos. At first, I thought that maybe Black women just didn’t attend. But it wasn’t that we were not there. We were there. In part, we weren’t documented because photographers and newspapers did not want to put Black women in their newspapers. Yet, that’s not the whole reason. There was a hidden, racist component of the women’s suffrage movement at the time – many white women did not want to march with Black women.

At the time, suffragette Mary Walton said, ‘As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.’

Black women were warned not to come, but they attended — they are the original “she was warned, but nonetheless, she persisted” way makers.

Today, we know at least 22 Black women showed up to the women’s march. At the first suffrage parade, the only African American organization that marched were Delta Sigma Theta Inc., all 22 founders marched. For white women marching, it was not easy, but for Black women, it was even more difficult.

More than 100 years ago, 5,000 women marched on Washington. But many of us were left out.

No more hiding, or feeling as though the things that changed ourselves should not be spoken about. A century from now, Black women who lost their children because of the contaminated water in Flint, Michigan will be archived. Black women who lost their children to police brutality, the dozens of trans-women who were murdered will be remembered. Queer Black women who have been abandoned by their families, women in wheelchairs and girls with disorders, will be at every march too.

For my maternal grandmother, Francila, who brought her entire family to a country for a better life. She walked the neighborhood of Little Haiti selling tissue paper for as little as $2 — I will march.

For the pregnant immigrant woman, I met while picking okra who could not bring a complaint against the farm owner for not providing protective gear — I march. For the baby girl she birthed with birth defects due to the levels of pesticide and not providing protective gear — I march.

For my 10 nieces, three sisters, all of us who have struggled with being left out — I march.

On the anniversary of the march, I hope that more Black women march. I hope that Black women bring the names and photos of the women who would not have been able to march. I hope that there are banners, posters, and bodies with lavender paint to represent Black womanism.

Let us commemorate this march by not only writing the names of our great-grandmothers who were forgotten but share data on how Black women and other marginalized women have been treated. Let us demand that there will never be another march without all women. No woman will be warned to not attend. No woman will be warned to stay behind for the advancement of a law that deserves to protect us as well.

I hope today, everyone marches for someone who would have been left out. And take lots of photos to document our existence as part of this movement. Because this is our march too.