The Women Suffragists You Don’t Hear About Enough

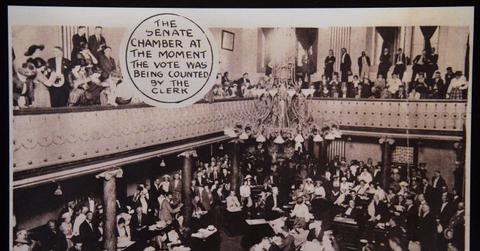

A full century ago, on August 18, 1920 to be exact, the 19th Amendment for the women’s right to vote was ratified by Tennessee’s legislature. Colloquially, the 19th amendment granted women the constitutional right to vote, however, the actual legislation states that no one will be denied the right to vote on the basis of sex. Although on paper this secured the largest enfranchisement in American history, the women’s right to vote was not inclusive to all women.

Throughout American history, notable names like Susan B. Anthony, and Alice Paul are taught as the leading trailblazers of the Women’s Rights Movement. Unfortunately, many other notable women that led the women’s suffrage movement have been negated in history conversations. Suffragists began their fight for women’s equality in 1848 although even today, we are still seeing the performative notion of our country’s leaders to amplify historical women that made it their mission to not include those that didn’t fit their agenda.

It is crucial to highlight that not all women were given the same privilege as white women when the 19th Amendment was passed. There were many women of color who were pivotal in the women’s suffrage movement we should recognize. The Women’s Centennial, a website commemorating the women’s right to vote, highlights the “extraordinary, dramatic, inspiring, complex, and too-little-known stories” through a blog series called, The Suff Buffs.

Unknown And Unsung Women Of The Movement

Black suffragist and civil rights activist, Mary Church Terrell advocated for racial and gender justice. After attending the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) she quickly learned Anthony’s platform excluded Black women. To encourage Southern white women to join the suffrage movement, Anthony advocated for the right to vote even if it meant accepting restrictions on voting including from poll taxes to literacy tests. She continued to call on women such as Alice Paul, imploring her to try to understand women’s voting rights from a perspective that argued voting rights for black women were inseparable from questions of black men’s disenfranchisement. In 1896, Mary Church Terrell became the first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW).

Since Terrell was one of the few African-American women allowed to participate in the National Women’s Party convention who could speak from the floor, she directly “addressed the Resolutions Committee asking for a Congressional Investigation. I said colored women need the ballot to protect themselves because their men cannot protect them since the 14th and 15th Amendments are null and void. They are lynched and are victims of the Jim Crow Car Laws, the Convict Lease System, and other evils.”

Terrell, despite Paul and other white suffragists’ racist dialogue and actions, she and allies such as Ella Reed Murray, consistently advocated for the interconnected issues of Black women’s disenfranchisement and the violence against them. She relentlessly delivered speeches at the conventions describing the gendered brutality, and other violent crimes to demand that gender and race be included in equality work. Terrell and other African American suffragists persisted in creating their own agenda in their work for women’s equality.

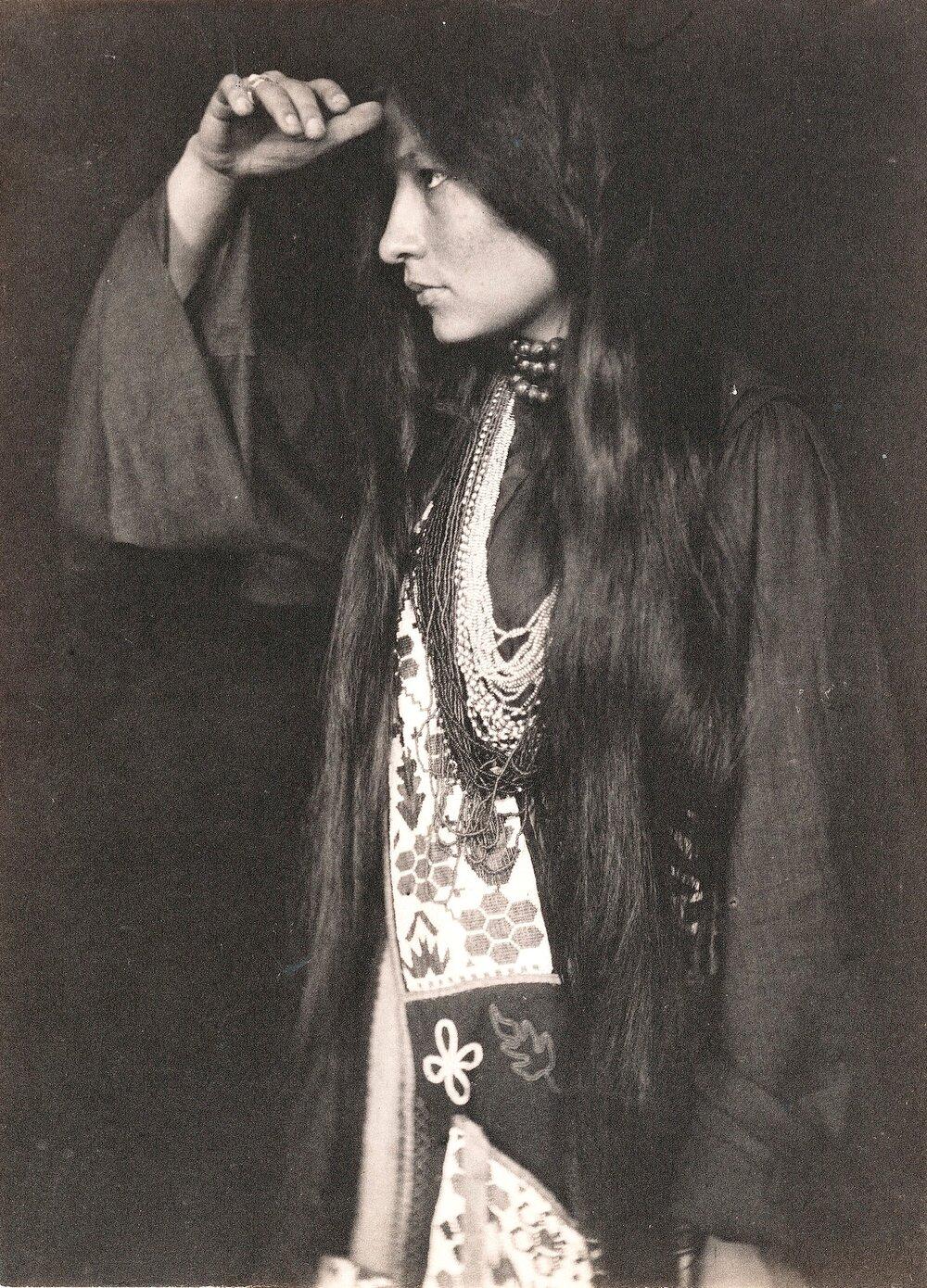

Suffragist and voting activist, Zitkala-Ša, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, is important to note in the women’s suffrage movement. She spent her lifetime advocating that she could be both a citizen of the United States and a citizen of the Yankton Sioux Nation (South Dakota). Growing up, indigenous people faced revolving policies that outlawed Native governments and placed them under “legal federal warship.” When Zitkala-Ša was a child, she was forced to abandon her heritage and sent to a Quaker boarding school in Indiana for an education. After becoming a writer and advocate, she helped lead the passage of the Indian Citizen Act and Indian Reorganization Act.

Despite the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 denyingMabel Ping-Hua LeeAmerican citizenship, Lee and other Chinese-American women marched in one of the biggest suffrage parades in U.S. history, the New York Suffrage Parade. Being one of the only Chinese women, Lee was invited to speak to the Chinese community, particularly around immigration laws. She was sixteen at the time of her speech.

Honoring The Generations Of Women That Fought For Us Now

In the great words of founder of the Alpha Suffrage Club, Ida B. Wells Burnett, “with no sacredness of the ballot there can be no sacredness of human life itself.” We cannot forget the suffragists that carved the path for all communities that faced oppression and injustice. Many more women fought for the right to vote and promoted diversity and inclusion in the United States, speaking to the needs of their communities in order to thrive.

Let’s use the power these women have given us in November and vote for our generation, those before us, and those after us.