The Modern Effort To Preserve The Legacy & Estate Of America’s First Female Self-Made Millionaire: Madam CJ Walker

Often, when we want to remember something important we keep some sort of a memento. From photographs to physical items we keep things close that help us to relive a special moment in time. However, nothing makes the memory more real than physically revisiting the location. Touching it, seeing the sights, breathing the smells and more importantly feeling the spirit of the place.

Some things are harder to remember than others, not for lack of trying, but when the physical structures and mementos disappear, sometimes the stories start to feel more like just stories rather than something that was once real. When it comes to stories of great achievement and triumph that are part of the thread of history of Black people in America the physical structures that served as the homes of black leaders, or the locations of major black history moments are often lost. The history is essentially demolished, passed over or forgotten. So when we come across a rare treasure like the 34-room Italian style mansion known as Villa Lewaro built for and owned by the iconic Madam C.J. Walker in 1918, serious attention must be paid to preserve it.

Luckily for the past twenty years, Walker’s home has been properly preserved and cared for by the current owners Ambassador and Mrs. Harold E. Doley Jr. Before the Doley’s stepped up, the previous owners weren’t particularly committed to preserving the legacy of the Walker home so over the years a lot of work was needed to upkeep and restore the historic fabric of the residence.

“It’s been a labor of love bringing the property back,” explained Doley before a small group of media during a recent press tour. “It’s my wife and I..two dogs, two houses, 20,000 square feet, four floors, an elevator, nine or ten bathrooms, I think it’s more than two people need.”

And as Ambassador and Mrs. Doley enter retirement, the burden of maintaining the home and the responsibilities of keeping up with expenses and taxes are becoming heavier by the day.

“The politicians of Westchester are not kind to people that have big houses, they make you pay confiscatory taxes, and we’re working with Brent, The National Trust, The Rockefeller Brothers Fund on trying to determine the future of the Villa and we’re looking for ideas and thoughts to make that the stepping stone to the next level,” Doley went on to explain. “That’s why we’re here today.”

Brent Leggs and Jessica Pumphrey of the National Trust for Historic Preservation have stepped in to help with the process. To start, the Pocantico Center of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund hosted a retreat at the home in May with leaders from across the country to drum up ideas to generate income for the home while still preserving Walker’s legacy. A report is coming this fall, however, the National Trust is also considering ideas from the public. Some initial ideas being considered include turning the space into some sort of incubator for entrepreneurs, a retreat site, a spa, a conference center, or an event space.

“She was a sharer,” explained Doley. “This home represents a lot of different things. More than just [the structure] itself. Irvington which was named Dearmond in 1900, was the richest per capita community in America. So Madam said this is where I should build my home. She bought the land, she paid the black tax, which was basically more than double the going rate, and she hired a black architect.”

That architect was Vertner Tandy, who is one of the co-founders of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. and was one of the first members of the American Institute of Architects. Located just 45 minutes from Grand Central Station in New York City by train, the home is truly a physical tribute to the life and the grand vision of the most unlikely entrepreneur.

As Leggs explained the history of the home and the impact of Walker’s work, he recited a quote that captures the weight of the significance of preserving the physical legacy left behind by Walker. American scholar James Horton once said “a single visit to a history site makes a life once lived real.”

And oh, what a life Madam Walker lived! In an era where she utterly had no rights as a black woman in America at the turn of the 20th century Madam C.J. Walker did the unimaginable: she started her own business and went down in history as the first American woman to become a self-made millionaire.

Like most entrepreneurs, the inspiration to launch her company emerged from seeking a solution for a personal problem. After encountering an issue with hair loss, and trying everything that was out there to no avail, she began to develop her own treatment leading to the creation of her signature “Madam C.J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” She launched in 1905, and just a few years into it she had thousands of women selling her products across the country.

“I think most people when they hear the name Madam Walker they think, ‘oh! She’s the hair lady!,’” explained Madam Walker’s great-great grandaughter A’Lelia Bundles, who also accompanied us on the private tour. “And they may even think, ‘oh! she invented the hotcomb.’ She did not invent the hotcomb.”

Indeed, her pioneering endeavors in the haircare industry is just scratching the surface of the incredible story of grit and perseverance of this black woman who made her own way as an entrepreneur at the turn of the twentieth century. We have to remember, she was born in 1867, and she launched her company in 1905–women still did not have the right to vote and black people were legally discriminated against simply because of the color of their skin.

Before she changed her name, she was simply Sarah Breedlove, the first free-born child in a family of former slaves on a cotton plantation in Louisiana. Unfortunately, she lost her parents at age seven, and did not have access to a proper education because she had to work in the cotton fields. She married at age 14 to escape abuse from her cruel brother-in-law and became a widow with a daughter at the age of 20. From there, her story’s tide began to turn when she moved to St. Louis working in her brother’s barber shop making $1.50 a day — enough to send her daughter to school and take up night classes.

The story is almost impossible to believe. How could one woman– born on a cotton plantation in Louisiana, growing up without parents, and without access to a formal education muster the strength to overcome such massive obstacles? But the story of her life became incredibly real to me as I walked through the black iron gates and looked upon the incredible 20,000 square-foot mansion she called home.

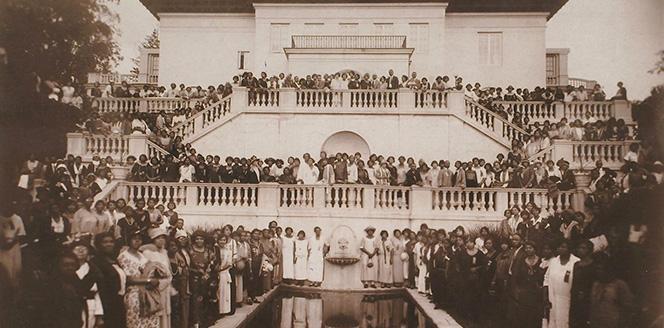

Madam Walker moved into the home in 1918 and died in the master bedroom in 1919 but following her death, her daughter A’Lelia Walker maintained ownership until her death in 1931. As I walked from room to room, I realized that many historic leaders from our past had walked these very same halls. As we stood in that legendary music room, Bundles told us of how her namesake A’Lelia was affectionately known as the “Joy Goddess of Harlem” and all about how she hosted legendary parties at the home during the 1920’s. I stood under the same crystal chandelier where the likes of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston had danced and walked through the same room where parties were held entertaining prominent leaders from the Harlem Renaissance.

Keeping the history of this country in mind as you move through the home using the marble staircase, and walk through the various floors and into the rooms with hand painted ceilings and gold foil column embroidery along the walls, you see not just an amazing house, but the physical manifestation of a woman with strength and fortitude. Although society viewed her as less than, she had a greater vision for herself and a desire to inspire generations to come.

Even the smallest details were grand. For example, in her bathroom, she had a customized steam shower complete with a full rainforest shower head. To this day, it’s still fully functional.

“There is no royal flower-strewn path to success. And if there is, I have not found it for if I have accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard,” is a famous quote attributed to Walker.

At Her Agenda, we often speak with successful women and talk about their path, and obstacles they’ve overcome to achieve their goals. Delving into Walker’s story the path she had to walk to achieve all she did was the rockiest imaginable. And yet, she simply used her obstacles as fuel to become a successful entrepreneur and more.

“In addition to being an amazing pioneer of the African-American haircare and cosmetic industry she also was a patron of the arts who supported young African-American musicians and actors,” Bundles explained. “She was a political activist who contributed a great deal of money to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund. She was an advocate for women’s economic independence and provided jobs for thousands of African-American women. People want to pigeon-hole her as somebody who was the hair lady but she was in fact a pioneer of the hair industry, but she also was an entrepreneur, a philanthropist, a political activist.”

At the end of the tour, Leggs took a moment to read a section of her last will and testament:

“The madam is grateful to her Creator that he has permitted great good to flow uninterruptedly to her. In turn she will give the beautiful palace in trust to her race, after the life of herself and that of her daughter. As she thinks of it now it will be held in memoriam of her – a museum or monument – where in after years members of her race may pilgrimage to it, prodding him to renewed energy because of the realism of such a grand result.”

At the time of her death in 1919, Walker had trained nearly 23,000 women. But in terms of her physical legacy, the Villa Lewaro, its ultimate future has yet to be decided, but if you’re so moved, you can help contribute your own ideas (or even a monetary gift) here.

“The threat is not right now, thanks to the stewardship of the Doley family, we’re looking towards the future,” explained Leggs. “The property sits right now without and easement to protect it. So the next buyer that acquires the property could negatively alter the physical and architectural integrity that you see here and potentially could demolish it so we want to make sure that never happens.”