Adjoa B. Asamoah wears many crowns. The daughter of activist parents – her mother a child in the Jim Crow South and her father a child in what would become the Republic of Ghana – social justice and activism is in her DNA.

Known globally as the CROWN Act champion, Adjoa started the national effort to eliminate race-based hair discrimination and the related CROWN Coalition in 2018. She served as the Biden-Harris Campaign’s National Advisor for Black Engagement in 2020, spearheaded a legislative victory to codify the nation’s first Office on African American Affairs, and was named one of the most influential 100 Black people globally by EBONY magazine in 2021 for her social justice work.

Adjoa joined us to discuss finding her why and getting comfortable doing uncomfortable things to make widespread, lasting social change.

Her Agenda: As someone who has made her mark by multitasking, how did you explore your identity growing up?

Adjoa B. Asamoah: I was born into a home where doing stuff to move people forward was just the norm. My dad is now a retired Africana Studies and Political Science professor and is someone who is a globally respected scholar-activist. So, I don’t remember a time when I didn’t think it was my responsibility to work to create the society that we wanted to live in. By the time I was two, I had already gone to my first rally – on my dad’s shoulders, against my mom’s wishes. By five I was in college classrooms learning about political systems in the world. We did not have money, but I was so rich with resources in the sense of self-identity that I didn’t really know we were poor. My “aha” moment was when I was nine: I had visited where my mom was born in the south, where you can’t see your hand in front of your face just because there are no streetlights, and I visited the birthplace of my father in Ghana and I saw Black people struggling in both places. Growing up in a household where my parents instilled this great sense of self pride that led to me having a real sense of self-identity, I noticed that Black people were struggling in both places. You’re talking about: in two different countries and two different continents and in two different hemispheres of the world, you mean to tell me Black people are struggling? And that struck a chord.

So very early on I understood this sense of anti-Blackness as a global issue. I already had a sense of global citizenship. So while racial equity has been my life’s work, before it was something that was popular or profitable or considered even appropriate to say, I also grew up with a father who made the distinction between culture and ethnicity and race, and made sure I understood that race was something that was socially constructed. There’s no biological basis for race the way we talk about it. And [I understood] that there’s a human race. But it doesn’t mean that you deny your culture, it doesn’t mean that there’s this hierarchy of society, but that there literally is just one human race. He taught me that we have these fights that are rooted in something that is not real in the way we talk about it, but racism is very real.

In Ghana I went to what some people call slave castles but they’re more like dungeons. They’re where African people had been held captive to board ships in the most inhumane way that anybody could ever imagine, times ten. They’re dark, they’re cold, even in Ghana. I went to what’s called ‘The Door of No Return,’ where my ancestors would go through and board a ship, chained to other human beings to be dehumanized, raped, brutalized, separated from family, treated as property, not human beings, being fed barely scraps to just survive… nothing nutritious to survive a transatlantic enslavement trade where your body is deemed as capital. I went through that space and I had my ‘aha’ moment.

If you go to a space like that, with a history professor dad, and you’re asking questions with your little nine-year-old capacity to ask these questions about what do you mean that this is what they did to people? What do you mean that this is the number of people that were in this room?

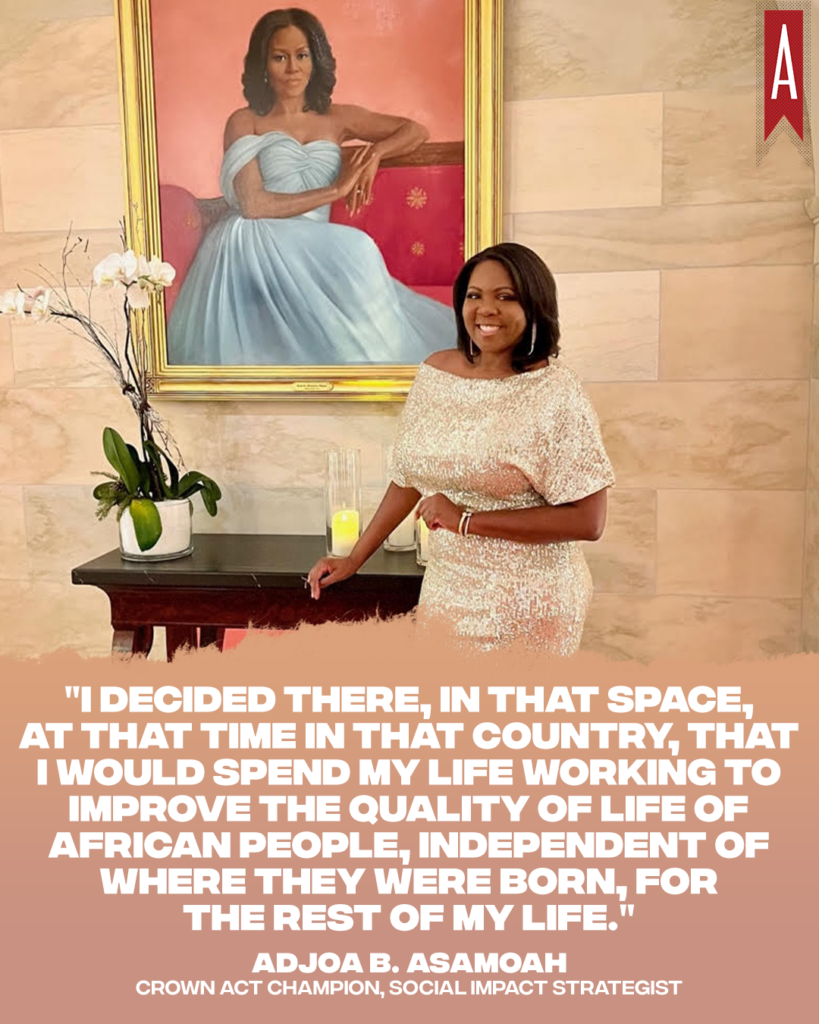

I decided there, in that space, at that time in that country, that I would spend my life working to improve the quality of life of African people, independent of where they were born, for the rest of my life. It would go on to take many different forms, but I knew that that is what I wanted to do.

Her Agenda: As someone with a life mission of improving the quality of life for others, what actions did you take to do that?

Adjoa B. Asamoah: When I went [to Hopkins School], I was the president of the Black Student Union and that was where I had my first movement idea. It was a private day school in Connecticut that used the language ‘headmaster’ to describe the leader of the school. Having knowledge about enslavement, ‘headmaster’ is not language I’m comfortable using. When I was not in class I was doing work study in the front office. I explained my positioning and that became my first movement. I was a work study kid and I said, I don’t like this language. They did not change the language while I was there, but I am the first person, to my knowledge, to take issue with the language and now the title is Head of School. It’s no longer ‘headmaster.’

I’ve never had a problem with speaking up or talking about things that people were afraid to talk about. I’ve never been afraid to say, ‘This is wrong.’

Her Agenda: How did you translate these early experiences of forming your identity into your professional aspirations?

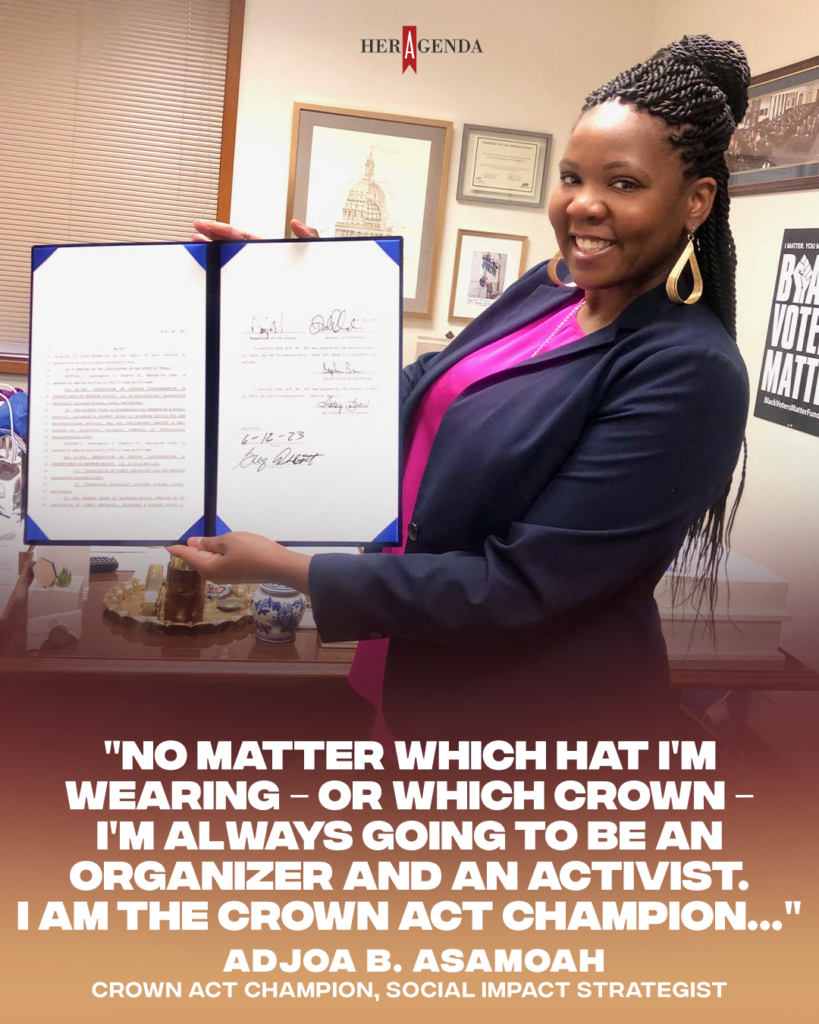

Adjoa B. Asamoah: No matter which hat I’m wearing – or which crown – I’m always going to be an organizer and an activist. I am the CROWN Act champion: I lead a national movement in an effort to outlaw race-based hair discrimination across the country. There’s no way I would have been able to do that if I didn’t have organizing skills. It’s an idea that I personally came up with, so if I didn’t have an appreciation for, or an understanding of, policy and activism and the way in which the two have to go hand in hand, I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish what I’ve accomplished. But I am also a licensed clinician. Three of my degrees are actually in psychology, one is in African American Studies, and whenever I defend this dissertation I just submitted, I’ll have a doctoral degree as well. But no matter which hat I am wearing, organizer and activist will never leave.

I was also the national advisor for Black engagement for the 2020 Biden-Harris campaign and you [need to] know how to organize people if you’re gonna do engagement. So of course, I leveraged those skill sets. I was the Black engagement director for the Presidential Inaugural Committee. You have to know how to organize in order to do that. Coalition-building skills is something that I picked up very early because by age seven I was full-blown organizing, and organizing requires you to interact with people and to build coalition and find places and points of commonality.

Her Agenda: You’ve worked in educational settings, clinical settings, political settings, the entertainment industry… the list goes on. How do you decide when and where to make your next career move?

Adjoa B. Asamoah: My why never changes, but my how continues to change. When people ask ‘What are you going to do?’ – I don’t know yet. I’ll know when it comes to me. My why is consistent and if you never lose your why you’re okay. Just know why you are doing what you’re doing. Your how, your strategy, all of those things can evolve. But my why is still the same. I will always work to create the society that I want to live in. It certainly has not been profitable to be this scholar-strategist-activist but there’s no divorcing me from my why. I won’t take on a role unless it’s in alignment with my ‘why.’ So, I just live this assignment-based life. We know that there are a number of racial gaps across spaces. We know that there are a number of gender gaps across spaces. So I’m trying to narrow those gaps, to put Black people in a different position across gender, to put women in a better position across races, and trying to make the world more equitable for Black people and women, with an obvious focus on Black women considering my own intersectionality in terms of my identity.

Her Agenda: One of the spaces where you’ve had a global impact is with the CROWN Act and the CROWN Act Coalition. How did that movement come about?

Adjoa B. Asamoah: The CROWN Act is a movement that I have led since 2018 when I personally came up with the idea that policy change was the best way to begin to try to tackle this very long standing and problematic practice of race based hair discrimination. I was working with some women who are phenomenal and I realized this has to be done through a policy change. That is a skill set that I have that is pretty unique: it’s problem identification, studying it – because I’m just a nerd and that’s who I am, I’m comfortable in that identity – figuring out what’s being discussed in the public discourse and then building my strategy around it. Part of my strategy has been about coalition building, so I also co-created what’s called the CROWN Coalition and leveraged my personal relationships and credibility as a lifelong racial and gender equity champion, and the work that I’ve done working at the intersection of policy and politics, to bring together the overwhelming majority of the organizations that constitute the CROWN Coalition, which is an alliance that is dedicated to outlawing race-based hair discrimination. That movement is important to me. I am globally known as the CROWN Act Champion because it’s a movement that I lead and an idea that I came up with to change the law. I developed the legislative strategy, the coalition-building strategy, the social impact strategy, and I lead that movement across the nation to make it illegal to discriminate based on hair texture or protective styles.

I am extremely proud of that work. I have done that work continuously since 2018. So when we talk about wearing hats the same way that I say no matter what I’m doing, I will always wear the activist hat, the organizer hat, strategist hat – I will always be the CROWN Act Champion. I’m still working to outlaw race and hair discrimination, and I always will. Being the CROWN Act Champion is something that I am very proud of. It’s a blueprint for how you champion change. I am an individual who had an idea. Had I not done what I had done and had the upbringing that I had there would be no CROWN Act.

Her Agenda: What advice would you give to people who look at your career and hope to do something similar?

Adjoa B. Asamoah: You don’t have to have a lot of money, or a fancy title, or be of a certain age, or a certain race, to be able to spark change. You, as an individual, can spark change. You have to determine your why, assess the problem and accept the challenge. Many people see your problem and they don’t accept the challenge. They know it’s a problem and they know something needs to be done but they don’t do anything and they wait for the next person to do it. Don’t wait for somebody else to do it. We’re waiting for you to do it.

[Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]