ANXIETY & AMBITION: The Reality Of An Invisible Disability

This article is part of our Anxiety and Ambition series where we explore the hardships and the emotional ambivalence of having anxiety while also wanting to achieve big goals.

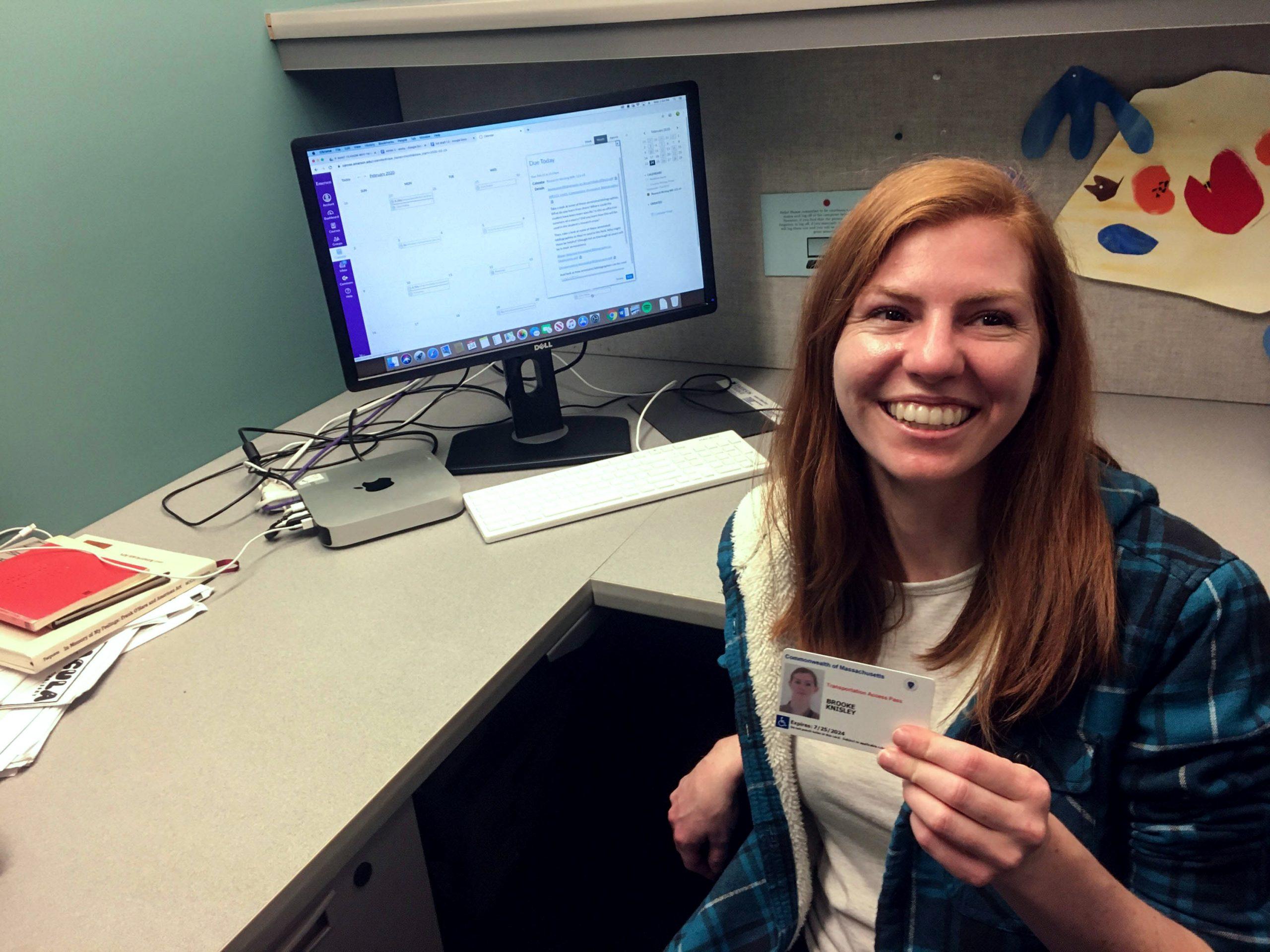

Brooke Knisley knows what it means to hit the bottom, literally.

In 2015, she fell from a Redwood tree on the University of California Santa Cruz campus after getting drunk, her usual state of being, she described in a recent interview with Her Agenda. The accident resulted in Knisley going into a 10-day coma, followed by a month of in-patient rehab.

She came from a military family with a history of mental illness. Combine that with the alcoholism, limited finances, and lack of consistent community due to moving often, and it’s not hard to understand why Brooke Knisley has faced a lifetime of anxiety, depression, and personal trauma.

Facing The Reality Of Long-Term Struggles

One of the major long-term results of Knisley’s accident is that she now deals with an invisible disability that affects her daily life including work and relationships. She had to relearn many day-to-day functions through a rehabilitation program and intense personal efforts.

“I continued to practice writing by hand and doing eye exercises [I had double vision], building core muscles and [correcting] my abnormal gait, and completing logic puzzles, and planning my life to improve my brain’s executive function. Nine months after my accident, I had an eye muscle surgery in April of 2016 to correct my double vision.”

It’s been a long road to full recovery, which has yet to be attained. Her anxiety was about the past, but now, it primarily involves the physical disability she sustained but no one sees.

Knisley lives in Boston and much of her daily anxiety comes from commuting via public transit to and from her job at Emerson College, where she teaches first-year writing.

Anxiety Erupts In Ordinary Places

“I get anxiety when I ride the T [Boston’s subway] because I hate being an inconvenience, but I really need to sit because of my [balance issues]. I don’t look disabled so I don’t want to ask people for a seat if there isn’t one and I’ve had people ask me to move…so they can sit. I’m always preparing myself for these situations, but I inevitably fail to say I need my seat and end up moving/shaking from the exertion it takes to maintain my balance,” she explains.

She further describes “large crowds and cross-talk also confuse and overwhelm me. At the end of last year, Emerson College put on its annual showcase for first-year writing students and I became so anxious and overwhelmed in the crowded event room that I hid in the balcony seats until it ended.”

This anxiety impacts Knisley daily, not just on the train and within large crowds. At work, her anxiety hits hard too.

“Before disclosing my disability to the first class I ever taught at Emerson…I’d have anxiety before each session. How could I conduct the class seated and without writing on the board?”

Her disability impacts her fine motor skills, preventing her from being able to write on a whiteboard or jotting down notes for students. She’s noted that this has made her feel “…like I [am not] a good teacher and [I am] a fraud—a writer who can’t write?!”

Taking Steps To Cope With Struggles

But Knisley is teaching. She’s facing the anxiety, the depression, and the history of trauma that would have held back many from having any kind of healthy, happy life. She takes special precautions to deal with anxiety, knowing specifically what causes her so many of the issues.

“When I can, I take a walk or do my best to get away from other people (whatever that involves). Other bodies exacerbate any anxiety I’m feeling since it normally overwhelms me, managing my own stress and then the perceived reaction I have from surrounding people. This doesn’t work when I’m teaching, for obvious reasons, so I always have small group activities planned or a relevant video to show; this gives me a moment’s reprieve to collect myself.”

According to Rebecca Sinclair, Ph.D., the Director of Psychological Services at Brooklyn Minds Psychiatry, P.C., “anxiety is often in the form of ‘what if’ thoughts or worries about potential future catastrophes. Anxiety tends to keep us on a loop of what if, but it can be very powerful to answer the question.”

“[Ask] yourself purposefully, ‘What am I afraid will happen?’ The difference between ruminating and managing your anxiety is trying to thoughtfully answer and then [plan] the next step,” she explains.

Dr. Sinclair recommends that if you are feeling anxious that you will embarrass yourself in front of new people, answer the question and figure out your next step.

“If the answer is ‘I’m afraid people will ask me questions I can’t answer,’ make a plan of how you will handle that. Maybe you will make a plan for how you will respond to them, like planning to say, ‘That’s a great question and something I need more time to think about.’ Or maybe you will plan to remind yourself that you can’t know what other people think about you.”

Knisley has done exactly this in her own career as a writer and educator at Emerson. “When I finally admitted why I couldn’t do all of these things, my class was so cool about it [that] I’ve made it standard protocol for each subsequent class – more for my mental well-being than the students. I don’t think they really noticed until I pointed it out.”

Finding Support In Each Other

Another component of preparing yourself for anxiety, specifically regarding your career, is done by seeking out and offering support to one another.

Dr. Sinclair says, “Women and non-binary folks often have had the experience of being told their emotions are ‘just’ their anxiety. The ‘j-word’ as I like to call it tends to be invalidating and has a rebound effect on their anxiety. That is, hearing that something is ‘just’ a feeling tends to make our minds and anxiety come up with lists of justifications and reasons why we are right to be worried, fueling anxiety and being overwhelmed.”

Validation and understanding one another’s experience is key in supporting each other through the anxiety, according to Dr. Sinclair.

“Validation doesn’t mean blind support or agreement. Validation comes from curiosity: listening openly to a person’s experience with a gentle curiosity about why they are struggling allows one to find [an] understanding of another person and gives them an opportunity for genuine validation on the emotion. It’s important to remember that you can simultaneously disagree with a person’s actions while at the same time understanding the emotions of the action.”

Anxiety Won’t Hold Her Back

Knisley has big plans and dreams. “I’m working on a memoir right now that deals with my depression and volatile upbringing, my accident and the resulting brain damage (plus the fallout from that), and what incorporating and acknowledging all of these facets of myself—disability, depression, alcoholism, etc., deemed negative by society-at-large—has meant for my identity and well-being.”

Knisley says she’s quit drinking and finds joy in being able to write.

“So, my big goal is to have that story told; for people to understand we’re all ‘broken’ in some way, but that’s fine because fragments and pieces are what constitute everything.”

Do you have a story or experience to contribute? Apply here to be a contributor and indicate in your application that you’d like to contribute to this series.