Impostor Syndrome: Why Women in the Workforce Are Filled with Self-Doubt

“I am not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people,” John Steinbeck wrote in his diary in 1938.

Maya Angelou once shared, “I have written 11 books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.’”

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg echoed these writers’ thoughts during a public speech by saying “There are still days when I wake up feeling like a fraud, not sure I should be where I am.’’

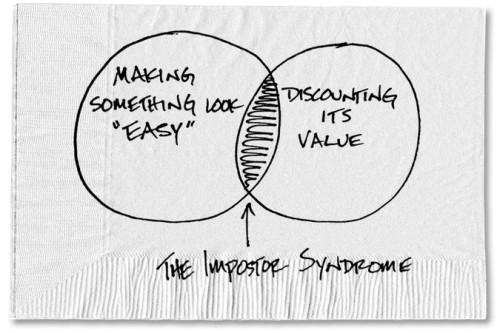

How could two of the greatest American authors not consider themselves writers? How could one of the most successful businesswomen in the world not consider herself successful? Impostor Syndrome, first coined in 1978 by clinical psychologists Dr. Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes, refers to the inability of high-achieving people to internalize their accomplishments: the persistent feeling that one doesn’t deserve to be where they are in life. Sound familiar? Researchers believe at least seventy percent of people have suffered from “impostorism” at least once in their lives.

But many people think that “syndrome” is a misnomer; it isn’t a mental illness or a complex or a syndrome, but rather an identifiable phenomenon that everyone experiences. These feelings of self-doubt can range from your shyness at an intimidating party to the overwhelming feeling that you’re an idiot when you’re surrounded by über smart people. However, the most popular usage of the term is the self-doubt that successful people feel when they finally reach their goals.

Throughout our entire lives we look up to inspiring people, work hard to follow in their footsteps, and aspire to reach what seems like an impossible place. We interview for that job and feel like we are lying through our teeth when, in reality, we are listing real-life and very honest accomplishments. We then get the job and feel like we tricked our way in. Or we get accepted to a college and are convinced that the admissions committee made a terrible mistake when they read the application.

“I don’t deserve this.”

“This makes no sense.”

“I was just lucky.”

No, they accepted you because they want you and you got the job because you are qualified. These climactic moments should be moments that prove our worth, but instead they make us question our worthiness all over again.

It’s no surprise that these self-deprecating thoughts are more prevalent among certain demographics. Sensibly, women often feel a heightened sense of fraudulence. In fact, its usage was originally only used in reference to women feeling out of place while working in male-dominated industries. While it is now agreed to not be a gender-exclusive phenomenon, clinical experience has shown it to occur in much higher frequency and intensity among women. In fact, Valerie Young authored a 2011 book titled The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women: Why Capable People Suffer from Impostor Syndrome and How to Thrive in Spite of It. Young says she ‘aimed the book at women…because chronic self-doubt tends to hold them back more.’

That’s not hard to believe at all. Despite the increasing success of girls in secondary school and universities (girls make up 70 percent of high school valedictorians), they still don’t feel like they belong once they enter the ‘real world.’ They are less likely to ask for a pay raise, apply for jobs at the upper echelons of management, or even stray from an institution to create their own company. In essence, they don’t have the confidence to pursue the dreams they are capable of achieving. And that’s a scary prospect — a world that is only reaping the talent of half of its population.

There is no question that women hold significantly less managerial positions — but is it stifling political progress by blaming it on their own chronic doubts rather than arguably prejudiced employers? We are still far from the end of that debate as a society, but it is still important that we do everything in our power to make sure women know that not only are they capable of breaking glass ceilings, but that there doesn’t have to be a ceiling at all.

A wide array of other factors can also cause someone to feel unworthy of their position in life. Perfectionism is often a common characteristic. The mentality that one needs to be the absolute best and the fear of any degree of failure sets one up for failed expectations. It’s like when we are on the first day of that job we “tricked” ourselves into, and we feel like our boss is going to “find us out” at any second because we don’t know how to do everything yet. High-achieving people are so accustomed to being experts in everything that any sign of unfamiliarity gives them the feeling that they are unworthy of their place.

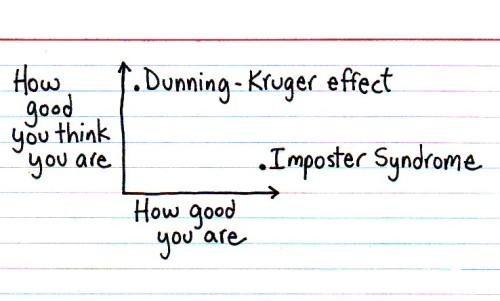

However, don’t be nervous if you feel like you fit the bill for impostor syndrome. At least you don’t suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect in which self-confident people are unable to recognize their own ignorance.

Jessica Collet, a professor of sociology at University of Notre Dame says “They don’t feel at all like frauds—they feel they know exactly what they’re doing and how could other people not know what they’re doing. But it turns out, they don’t know enough to know how little they know.” In essence, “people that are too dumb to know that they’re dumb.” We all know that person and we all hate them.

So, if you think you are doing everything right, maybe you should reevaluate. But the next time you feel like an impostor, just know that you’ve officially made it when you start questioning your greatness.