It’s Amelia Earhart, Not Mrs. Putnam — How Earhart Was Ahead Of Her Time In More Ways Than One

Having grown up a tomboy who climbed trees, sled down hills, and hunted animals, Amelia Earhart was no stranger to defying expectations.

As a child, she collected newspaper clippings about women in male-dominated fields who achieved success and hoped to be like them in some way. When she attended a stunt-flying exhibition at age 20, she knew exactly how.

Earhart took her first flying lesson on January 3, 1921. Within six months she managed to buy her first plane, a bright-yellow two-seater which she lovingly named “The Canary.” She used it to set her first women’s record by flying to the high altitude of 14,000 feet. However, this was only the beginning of what she would achieve.

Throughout her career, she reached new heights by setting multiple records not only for women, but for flyers everywhere. In 1928, she became the first woman to cross the Atlantic as a passenger alongside pilots Wilmer Stultz and Louis E. Gordon. She received a lot of publicity for this accomplishment from newspapers around the globe but it was still not enough to satisfy her desire for success. When she married George Putnam in 1931, the couple planned on making her the first and second person to fly the Atlantic solo.

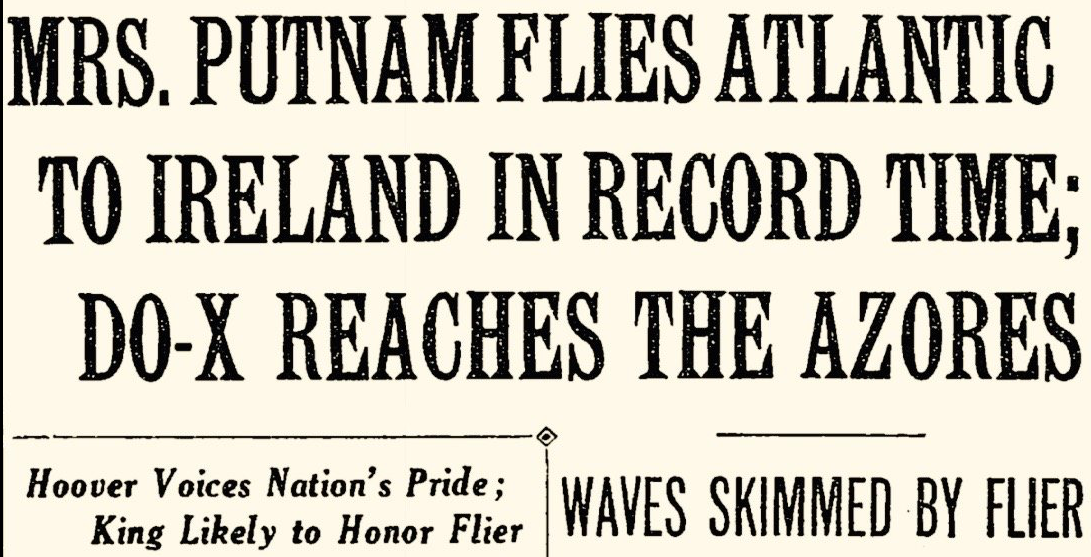

Earhart did not want her marriage to trump her individuality. She instead referred to her relationship with Putnam as a “partnership” to reinforce her refusal to compromise her ambition. However, many news publications did not honor this. Whenever anything was published of her accomplishments, newspapers would refer to her by her married name, not her flyer name. In 1932, when she achieved her goal of flying across the Atlantic solo, a New York Times headline celebrated “Mrs. Putnam” on this accomplishment, not Amelia Earhart.

Disturbed, Earhart took to writing Arthur Hays Sulzberger, the publisher of The Times. In her letter, she requested that she be referred to by her flyer name from then on. Earhart wrote, “It is for many reasons more convenient for both of us to be simply ‘Amelia Earhart.’ After all (here may be a principle) I believe flyers should be permitted the same privileges as writers or actresses.”

This request did not take immediately. In fact, the same day that Earhart wrote this letter, a headline was released in which she was referred to as “Mrs. Putnam.” However, within a few weeks she was again being referred to by her preferred name.

Earhart wanted to make it clear that her accomplishments were her own. There is a difference between publishing a story in which a woman sets a record and one in which man’s wife sets a record. By requesting to be referred to by her maiden name, Earhart made sure that people acknowledged her as her own person. She did not want to be overshadowed by her relationship to her husband and, because she had the courage to speak up for herself, she wasn’t.

In 1937, Earhart set out to be the first woman to fly around the world. It was during this flight that she and her co-pilot went missing. A rescue attempt was put in place immediately, which became the most extensive air and sea search in naval history. However, after spending 4 million Dollars and searching 250,000 square miles of ocean, the U.S. Government had no choice but to call the search off.

In 1938, a lighthouse was constructed in Howland Island to honor Amelia Earhart, not Mrs. Putnam, for all of her accomplishments.